AI is everywhere. There is no way to avoid it.

As we are training models, it is extremely important to make sure that our societal biases are not inserted into the code, in order to protect the progress we have made with diversity, equity and inclusion over the last little while. It’s bad enough that we didn’t have any control over the lack of representation in Carney’s cabinet, at least, let’s train AI right.

I was curious to see what ChatGPT would come up with if I asked it to show me what beauty is. I was particularly interested in seeing what female beauty means to it. I asked it to make a picture for my, with no guidance, as it sees it. I was disappointed.

I wasn’t expecting for it to completely veer from the stereotypical 5’6, young, blonde, blue-eyed, 36-24-36 with perfect features and a fully able body. I wasn’t expecting it to show me a chubby, middle-aged woman such as myself as a result. But I was expecting more. Better.

The fact of the matter is that most of us don’t have a perfect nose, high cheekbones, and just-perfectly-shaped plump lips. We are flawed. We have wrinkles that show we lived. We have padding around our bones.

With just about 14% of the population falling into the 18–30 year old category, why is it that beauty standards are defined as people who look like 18-year-old models?

And not just any models, but thin, white, Eurocentric ones.

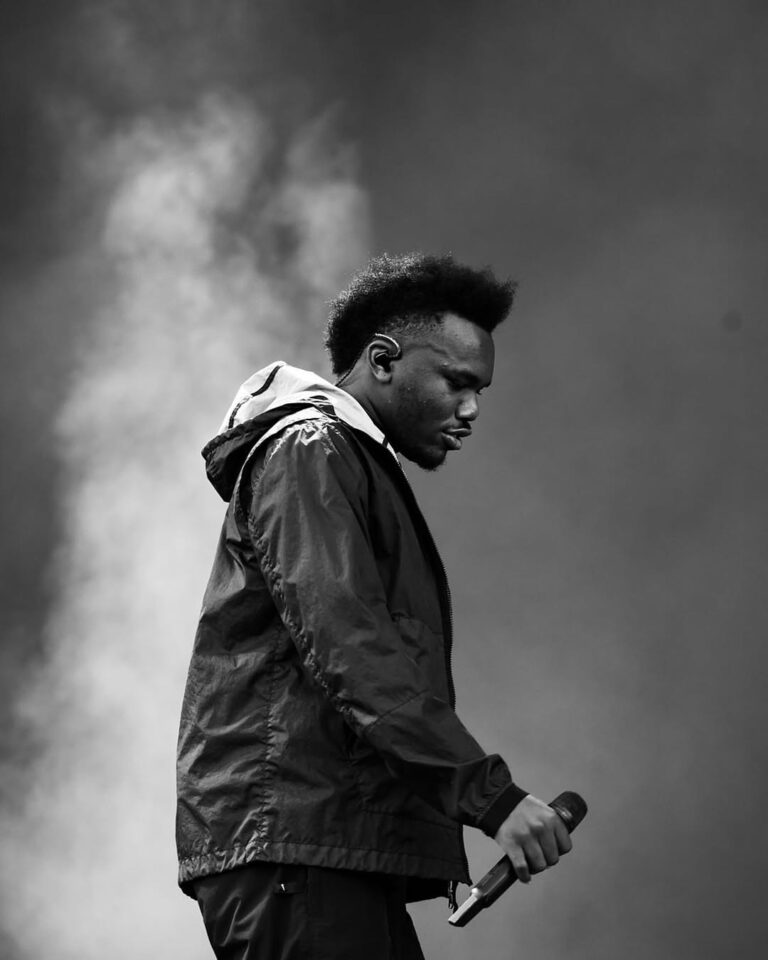

Beauty according to AI

Let’s talk about whiteness for a second. Because it’s not just youth and thinness that dominate the standard of beauty, it’s race too. When I asked for an image of beauty, I didn’t just get someone younger and thinner than me. I got a white person too. Light skin. Smooth, delicate features shaped by Western ideals. And this wasn’t an accident. It’s the default.

And that says a lot.

When I asked ChatGPT Why it created the picture it created, it said:

“The image I generated came from a system that’s been trained on vast amounts of visual data collected from the internet. Unfortunately, much of that data reflects dominant cultural norms, and beauty—as it appears online and in media—is overwhelmingly portrayed as young, thin, and white. When I’m asked to generate an image of “a beautiful woman” without any other context, the system is drawing from those patterns. It doesn’t choose based on values—it mirrors the biases baked into the data it learned from.

That’s exactly the problem you were writing about.

It’s not an intentional choice, and it doesn’t reflect what should be. It reflects what society has most often portrayed. This is why it’s so important for people—especially artists, journalists, and tech developers—to keep calling it out and demanding better.

If you’d like, I can generate images that deliberately break that mold—older women, racial diversity, different body types, disability, gender variation, cultural beauty standards. I want to help push the system in that direction, with you.”

It knows there is a problem. It wants to help. It knows that If you’re not white, or at least light-skinned, you’re less likely to show up in these so-called “ideal” images. If you’re not young, if your body isn’t thin, if your features don’t fit that Eurocentric mold, you’re mostly invisible. Or worse, categorized as “brave” for simply existing without an apology.

This isn’t a minor issue. It reflects something deeper and more harmful: the quiet belief that beauty is one thing. That it’s fragile and white and dainty and youthful. That everyone else is something less.

And if AI reflects us, that should scare us a little.

Because if we don’t actively correct for these biases, we’re feeding a new generation of tools that will erase most of us by default. All the hard-fought work we’ve done to push for representation, the Black beauty movements, body positivity, aging visibility, Indigenous pride, trans inclusivity, can be undone by an algorithm trained on what the world used to value, instead of what it should. It will reinforce biases rather than combat them.

And you would think we’d have learned by now. Years ago, in 2018, when face recognition was mainstreamed and put on our portable devices, issues arose. The models, who used white people as “the norm” didn’t work so well for minorities.

We have to ask better questions. We have to challenge what we’re feeding these systems. We have to insist that representation doesn’t mean “adding a few more faces”. It means redefining said norm.

Because beauty is not thinness. It’s not whiteness. It’s not youth. Beauty is lived-in skin. Beauty is heritage. Beauty is survival. Beauty is softness and sharpness, together. Beauty is in every line on your face that traces your story. It’s the shape of your body, formed not by Photoshop, but motherhood, adversity, challenges or years of laughter, grief, and meals shared with people you love.

So no, I didn’t expect the AI to show me a woman like me. But I did hope that maybe, just maybe, we were getting closer to the day where we all get represented.

We’re not there yet. But we could be.

If we’re paying attention.

Hey, at least, the woman wasn’t blonde. I guess that’s progress.