There has been a noticeable shift lately toward war talk. Not just about politics or global affairs, but about conflict itself. War talk is everywhere. It is casual. It is flippant. It is often framed as bravado, satire, or righteous anger. And that worries me.

We are living in a moment where real-world conditions are already unstable. Donald Trump has proposed a dramatic increase in U.S. military spending, calling for a $1.5 trillion budget in 2027 as global tensions escalate, while also openly discussing the possibility of the United States withdrawing from NATO and framing international relationships as transactional threats. Canada is increasing military spending and preparing for a less predictable global order. The European Union is reportedly cutting back on intelligence sharing with the U.S. because of concerns about reliability and security. Putin is still attacking Ukraine. Gaza is still burning. Tensions around Taiwan have not gone away.

This is the backdrop. And against it, we are increasingly surrounded by language that treats war as inevitable, exciting, cleansing, or even deserved.

The Normalization of War Talk

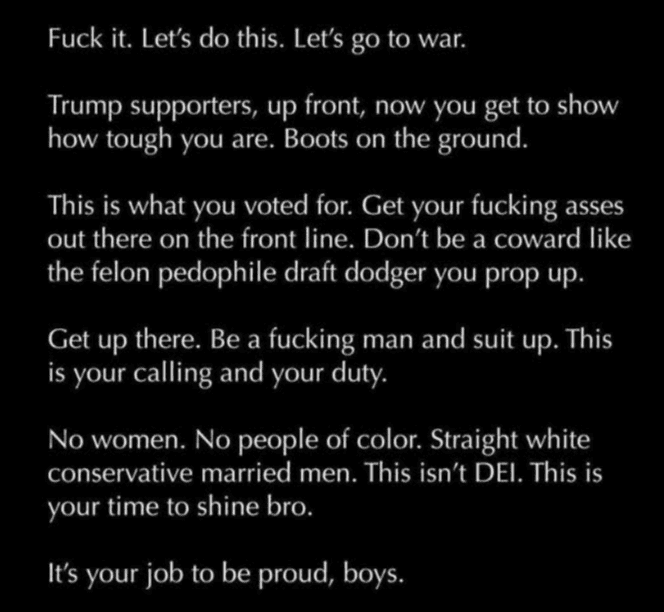

Scroll social media for a few minutes and you will see it. Posts daring people to “man up” and fight. Jokes about civil war. Irony-soaked calls for violence meant to expose hypocrisy. People talking about who would win, who should be on the front lines, who deserves what. Even when framed as satire or critique, the language is the same. It sounds like war. It feels like war. It primes the imagination for war.

This is how normalization happens.

War talk does two dangerous things at once. It makes the idea of war feel familiar and it dulls our emotional response to it. When conflict is constantly framed as something abstract, symbolic, or performative, we stop associating it with bodies, trauma, displacement, and irreversible loss. War becomes a concept instead of a catastrophe.

That desensitization matters – especially right now.

Why This Moment Is Different

We are not living in a calm or rational information environment. We are living in one shaped by outrage algorithms, grievance politics, and a growing number of people who already feel alienated, armed, and angry. Many of them are not reading carefully. Many of them do not recognize satire. Many of them are actively looking for validation that violence is justified.

In that context, the risk isn’t criticizing war. It’s criticizing it using the same language that fuels it.

There is a tendency, especially online, to assume a shared level of literacy or intent. To assume that people will “get the point.” But points do not land the same way when emotions are already heightened and trust in institutions is collapsing. A post meant as irony can just as easily be read as permission. A rhetorical provocation can become a screenshot stripped of context and shared as proof that “everyone wants war anyway.”

This is not about being fragile or censorious. It is about understanding the atmosphere.

The Cost of Treating War as Rhetoric

Language shapes how people feel long before it shapes how they think. When war talk becomes casual, it lowers the psychological barrier to accepting war as normal or necessary. It makes escalation feel less shocking. It turns the idea of mass violence into background noise.

Unfortunately, too many people think war is something other people fight. Other people lose children, limbs, homes, futures. Those costs are conveniently absent from most online bravado.

I am not arguing that anger and criticism are misplaced. They are not. I am describing what I’m seeing, and it scares me. In a moment that is this unstable, language does not just express feeling. It contributes to the climate we are all moving through.

Words matter because they shape how people think, feel, and interpret what is normal or acceptable. Right now, the conditions are already volatile enough.

There are consequences to what becomes normalized. Especially when it comes to war.