Billionaire preppers don’t always make headlines, but their escape plans are increasingly hard to ignore. In recent years, reporting has focused on billionaires investing in luxury bunkers, private islands, fortified compounds, and Mars colonization. Taken together, these projects point to a growing assumption that extreme wealth can insulate a small number of people from global collapse.

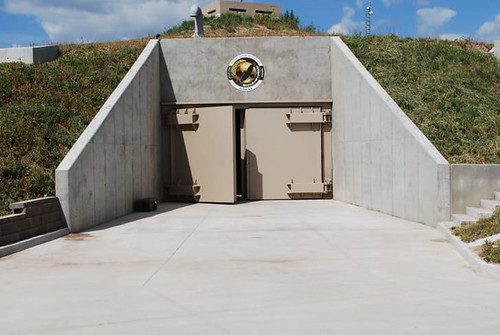

Over the last decade, reporting has documented Silicon Valley figures quietly buying land in New Zealand and installing multimillion-dollar luxury bunkers as insurance against what preppers call ‘the event.’ Peter Thiel acquired New Zealand citizenship and reportedly explored bunker construction there. Mark Zuckerberg’s Hawaiian compound includes an underground shelter stocked with food and supplies.

If this is the future, it looks less like progress and more like a very expensive panic room.

What interests me is not only the scale of these investments but also what they reveal about how the future is being imagined. These are not signs of confidence in shared systems or collective solutions. They suggest a belief among the very wealthy that a collapse is imminent and that the rational response is not repair but exit.

I find that belief fascinating, and deeply flawed.

Societies are not simple systems. Survival is about more than concrete walls, stockpiles of food, or clever technology. It depends on relationships, cooperation, trust, and functioning shared systems.

So the question is not whether billionaire preppers’ fantasies exist, but whether they actually make sense. Can anyone really escape a collapsing planet, or is this another delusion made possible by entitled insulation from ordinary human life?

Wealth as False Superiority

We live in a culture that constantly equates wealth with superiority. Over time, we’ve been conditioned to believe that money is a sign of intelligence, capability, and fitness to lead, especially when things get hard. That the people who hold the most resources are naturally better suited to guide society through crisis.

I don’t buy that.

Money did not begin as a measure of human worth. It began as a system of exchange. In modern capitalism, its accumulation functions as leverage. It grants power within a specific economic system, under specific conditions. It is not proof of resilience. It is not proof of wisdom. And it is certainly not proof of moral clarity or long-term thinking.

In fact, many of the traits that help people accumulate extreme wealth are poorly suited to moments of systemic stress. Competition over cooperation. Extraction over care. Short-term gain over long-term stability. Distance from consequences rather than accountability. These traits can produce fortunes, but they do not reliably produce survival.

When our social systems begin to break down, the rules change. The qualities that matter most are trust, adaptability, shared responsibility, and the ability to live within limits. These are precisely the qualities that billionaire preppers’ plans tend to ignore or undervalue.

Billionaire Preppers Choose Exit Over Repair

Figures such as Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg are often framed as visionaries preparing for the future. Their ideas are treated as neutral or even benevolent guidance for what lies ahead. But their behaviour tells a very different story. Musk’s rhetoric envisions Mars colonization as humanity’s backup plan. Bezos believes in moving heavy industry off-world through Blue Origin. Thiel and Zuckerberg have invested in physical retreats designed to weather societal breakdown.

Rather than staying involved in the everyday work of keeping societies functioning through governments, public institutions, infrastructure, and social systems, these projects are about personal exemption. That choice reflects a worldview in which responsibility is optional, and consequences are avoidable for those with enough resources. Extreme wealth does not just enable escape. It normalizes the idea that withdrawal is smarter than repair.

What underpins this choice is a shrewd and heartless calculation. Staying and investing would mean accepting limits, public accountability, and shared outcomes. It would mean losing the ability to fully control the narrative and the exit. Escape preserves autonomy in the short term, even though it increases risk in the long run.

The Myth of Invulnerability

Billionaire preppers’ escape plans assume that elite control can be preserved. That environmental disruption, social unrest, political instability, and loss of public legitimacy can all be managed or avoided rather than confronted.

But power changes as systems change.

Elite power depends on stable institutions such as legal systems, enforcement mechanisms, financial structures, and political authority. Its legitimacy is maintained through those structures rather than being negotiated directly, face-to-face, with other people under stress.

Money loses meaning when there is nothing left to buy. Proximity strips away the illusion of powerfulness when elites are forced into direct relationships with others, without the buffer of status or institutions. Scarcity reshapes alliances in ways money alone cannot control. What looks like invulnerability is often just insulation, and when the systems providing that insulation begin to fail, so does the illusion of total control.

Why Billionaire Preppers’ Plans Fail in Practice

The problem with billionaire preppers’ escape plans is not that they are dramatic or implausible. It is that they are built on assumptions that only hold in a stable world. Bunkers, private islands, fortified compounds, and even off-world colonies all rely on the belief that survival can be reduced to infrastructure, technology, and distance from other people.

Isolation does not eliminate dependence. A bunker or island retreat still requires energy, maintenance, replacement parts, skilled labor, and functioning supply chains. Even extensive stockpiles assume a world that continues to manufacture what you did not anticipate needing, and remains stable enough to deliver it. Once that world begins to fracture, redundancy disappears quickly. What looks like independence is really deferred reliance.

Technology does not preserve authority under stress. Many billionaire preppers rely heavily on automation and AI to manage resources and reduce reliance on human judgment. While we can’t know for certain, we can imagine that automated systems would be designed to optimize for stability and efficiency rather than hierarchy or status. In prolonged emergencies, they would likely prioritize preserving the survival infrastructure itself—power, air, water, logistics—and the continuity of the enclave as a functioning unit, even when individual authority or preference conflicts with that goal.

Biology is another constraint these fantasies routinely underestimate. A virus does not need an invitation. It can enter sealed environments through staff, supplies, animals, or environmental change. Once inside, small isolated populations face limited diagnostic capacity and treatment options. Survival depends on access to broader medical systems and collective knowledge, not withdrawal from them.

Even the most ambitious version of escape, space colonization, fails on similar grounds. A Mars settlement would remain dependent on Earth for decades, if not longer. Every habitat, system, and repair depends on manufacturing, energy, and political stability back home. Any disruption turns routine maintenance into triage. There is no meaningful redundancy, only increasing fragility stretched across distance.

These failures are not spectacular. They are structural. They unfold slowly, through erosion rather than collapse, narrowing options over time rather than ending them all at once.

The Road Not Taken

What makes this turn toward escape so striking is that there is another path available. If even a fraction of billionaire wealth were directed toward strengthening shared systems, the perceived need for escape would diminish. Robust public health systems, climate mitigation and adaptation, resilient infrastructure, food security, and social stability are not abstract ideals. They are practical investments that reduce risk for everyone, including the wealthy. They work precisely because they are collective.

Some billionaires do invest in public systems. The Gates Foundation funds global health initiatives, though its approach has drawn criticism for prioritizing technocratic solutions over structural change. Bloomberg has funded climate initiatives. But these efforts remain exceptions, and they often operate within frameworks that preserve existing power structures rather than challenge them. The scale of investment in private escape infrastructure versus genuinely collective resilience reveals where priorities actually lie.

Choosing the collective path would not require martyrdom, but it would require relinquishing the fantasy of exemption. It would require staying, participating, and accepting limits rather than building around them.

For the rest of us, the choice is not about building bunkers, but about whether we support and demand investments in health care, climate adaptation, and infrastructure instead of applauding escapist vanity projects.

Who Shapes the Future, and Why That Matters

Billionaire preppers’ fantasies would matter less to society at large if they remained private. They do not. The same people building escape routes are treated as authorities on what the future should look like. Their preferences shape investment, policy priorities, and public imagination.

When speculative technologies like private space travel, artificial intelligence, and life-extension research are promoted as bold innovations, they are marketed as ways to preserve life in the face of growing terrestrial problems. In reality, they are designed to protect a narrow group of people with access and control. Public systems like health care, infrastructure, housing, and climate adaptation are also meant to preserve life, but they do so by reducing harm for everyone. Both are presented as solutions to the same problem. The difference is that one concentrates protection for the privileged few, while the other distributes it.

Concentrated and very expensive protection is framed as visionary, while collective protection is dismissed as slow, inefficient, or political.

Over time, this shapes what society is encouraged to see as realistic. As venture capital flows disproportionately toward AI, space technology, and longevity research, public investment in health care, infrastructure, or climate resilience starts to look impractical or slow. This is not accidental. It reflects whose priorities are being amplified.

It’s important to note that advice from people preparing to opt out is not neutral. It reflects the priorities of those escaping, not the majority of us who cannot afford to leave. When speculative technologies are repeatedly framed as visionary while collective action is dismissed as naive, the effect is insidious. It trains people to see their own power as inadequate and elite withdrawal as rational. Over time, this framing encourages passivity precisely when active resistance matters most.

The Cost to Everyone Else

There is a cost to billionaire preppers’ fantasies that rarely gets discussed, and it is not paid by the people building bunkers or buying islands. It is paid by everyone else.

When resources flow toward private escape infrastructure instead of public systems, the consequences are material. Climate adaptation, pandemic preparedness, and infrastructure maintenance require sustained public investment. As Douglas Rushkoff documents, wealthy preppers spend millions on bunkers while simultaneously opposing the taxes that would fund the collective systems their survival actually depends on. The resources diverted to private escape could fund water systems, housing, health clinics, or renewable energy projects that reduce the likelihood of the collapse they claim to fear.

In Conclusion

Billionaire preppers’ fantasies are not plans for the future. They are attempts to avoid responsibility for the present. They promise control and insulation, but collapse under the realities of shared systems and human dependence. The greater danger is not that a few wealthy people might leave. It is that we continue to treat them as guides to our future while they quietly abandon the idea of a shared one.

Survival has never been an individual achievement. It has always been collective. A future built on private escape is not a future at all. It is abandonment.