Overview

The expanded GST rebate is being sold as a practical response to grocery prices that remain high. On the surface, the idea is appealing. Food costs rose again through late 2025, and low and modest-income households are spending a far larger share of their income on groceries than they did even a decade ago. For families already stretched thin, extra cash helps. The rebate puts money into people’s pockets quickly by leveraging the existing GST rebate system and reaches millions of Canadians without new applications or delays.

But speed and simplicity are not the same thing as effectiveness. The harder question is whether the GST rebate actually addresses the reason grocery prices are so high in the first place. Canada’s food retail market is dominated by a small number of large companies, and that concentration shapes how prices are set and how quickly they fall, if they fall at all. When governments respond to that kind of market by sending cash to consumers, there is a real risk they end up subsidizing the system rather than changing it.

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s approach treats grocery affordability as a problem of whether families can stretch their pay cheques far enough, rather than a problem of why the prices on the shelves are so high to begin with. In the short term, that approach would help people cope. In the long term, it could lock Ottawa into a cycle of permanent rebates that grow every time prices rise, while the companies with pricing power remain largely untouched. Canadians will pay for those rebates through collective taxes, even as profits stay private.

The GST rebate may ease some financial pressures this year. The question is whether paying around the problem is the same as solving it.

NCRnow continues to cover affordability and economic policy issues affecting Canadian households.

What the new gst rebate actually does

The policy branded as the Canada Groceries and Essentials Benefit is an expansion of the existing GST/HST credit. Program details published by the Canada Revenue Agency show the plan would cost roughly $12.4 billion over six years and reach about 12.6 million people. Most of the money would come through a one-time top-up in 2026, followed by a permanent increase to quarterly payments.

For a family of four, support would increase to approximately $1,890 in 2026, before settling at approximately $1,400 in subsequent years. Singles and couples would see a similar pattern: a noticeable increase followed by a lower but ongoing increase.

From a governmental delivery standpoint, this is easy policy. Eligibility is already established through tax filings. Payments can go out quickly. No new bureaucracy is required. In a moment of widespread frustration over food costs, this would be helpful to consumers.

Why grocery prices keep rising

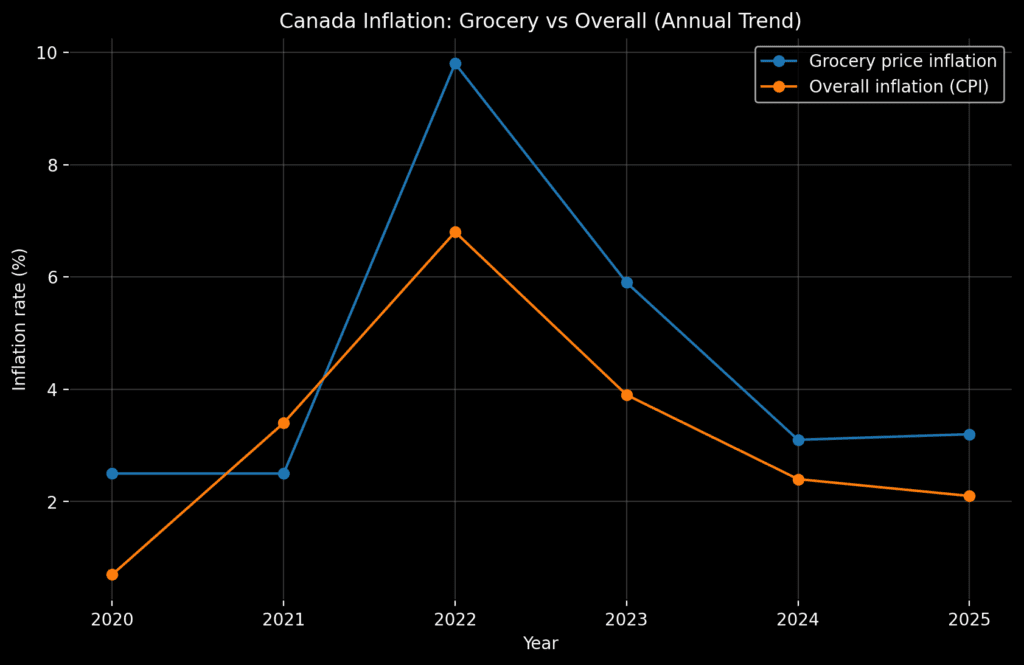

Grocery inflation has not followed the path many hoped it would. While overall inflation cooled through much of 2024 and 2025, food prices rose again towards the end of 2025. Statistics Canada reported that food prices were still rising, with prices roughly 5 percent higher in December 2025 than in December 2024, even as headline inflation slowed.

Some of the drivers behind higher grocery prices are real and difficult to avoid. Extreme weather has disrupted produce and coffee supplies. Beef prices climbed as North American cattle herds shrank to historic lows after years of drought, higher feed costs, and producers exiting the industry, a trend tracked by both Statistics Canada and agricultural reporting. A weaker Canadian dollar has also raised the cost of imported food. None of those factors disappears with a rebate.

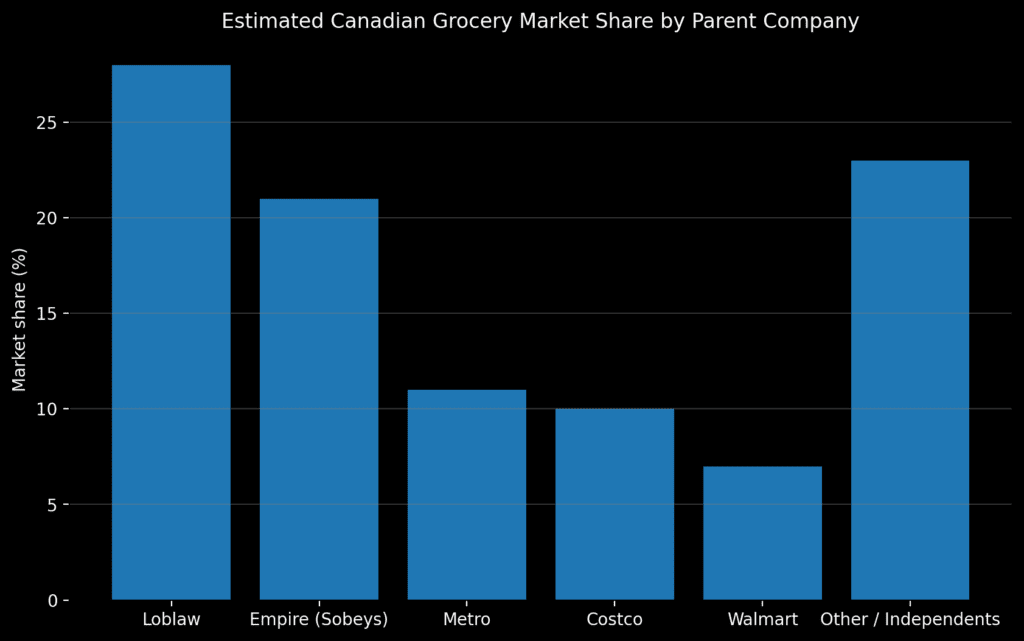

But these pressures exist inside a retail market that is already highly concentrated. Reporting by CBC and findings from the Competition Bureau show that a handful of companies dominate Canada’s grocery sector, with Loblaw, Empire (Sobeys), and Metro controlling the majority of the national market share. Discount outlets often belong to the same parent companies, which limits meaningful competition.

The risk of treating a market problem like a household budget problem

When governments inject cash into a market dominated by a few powerful sellers, they do not change how that market functions. They increase the amount of money consumers can spend within it. In competitive markets, where many sellers are fighting for customers, extra consumer spending can help push prices down. In concentrated markets, higher purchasing power does not reliably translate into lower prices, because dominant firms retain pricing power.

In plain terms, if a few companies control most of the shelves, those companies still decide what food costs. Research on pricing power in concentrated markets shows that consumer transfers do not reliably translate into lower prices unless competition or regulation constrains sellers. Nothing in the gst rebate prevents the money from flowing directly into corporate revenue.

A contrast worth considering: Avi Lewis and a public option

During his NDP leadership campaign, Avi Lewis has argued for a different approach: publicly owned or non-profit grocery options that sell food at cost. His proposal does not call for replacing private stores, but for introducing a credible competitor that could help discipline prices. Examples he cited included U.S. military commissaries and Mexico’s DICONSA system.

Critics of this idea point out that building a public grocery network would be expensive and slow. It would require coordination across provinces and municipalities, upfront capital investment, and years to scale. This is not a quick fix, and Lewis himself framed it as a structural project rather than an emergency measure.

There are also options that sit between cash rebates and publicly owned stores. Governments could support non-profit grocery co-ops, invest in regional food hubs, or use public procurement power to set price benchmarks for staple goods. In practice, this can mean governments negotiating large-volume contracts for basics like milk, bread, or produce for schools, hospitals, and long-term care, and using those prices as public reference points that suppliers must compete against. These approaches aim to change how prices are formed, not just how families cope with them.

So, is the gst rebate a mistake?

In the short term, the GST rebate could help people eat. When food banks are helping more working families, dismissing cash support outright would be dishonest. For someone choosing between groceries and rent, any extra money is welcome.

The concern is what happens when this becomes the default response every time prices spike. If grocery costs remain high because market concentration remains untouched, will Ottawa face pressure to top up the GST rebate again and again? If so, over time, this risks becoming an expensive way of avoiding harder policy choices.

Helping people cope is one role of government. Preventing the harm in the first place is another. Right now, Mark Carney’s plan leans heavily toward coping. While it may buy short-term relief, does it really buy long-term affordability?